The COVID-19 pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of life, and the court system is no exception. Judges have been holding hearings only for the most pressing matters, and most trials have been delayed or cancelled. Jury trials during the pandemic are especially problematic given the close proximity of jurors who often spend hours together in a jury box, followed by more hours or days conversing in a deliberation room. Indeed, courts are being forced to innovate to provide timely justice while minimizing the risk of infection to all persons involved in hearings – including court personnel and jurors.

One option to promote safety during and post-pandemic is to allow jurors, and possibly other trial participants, to attend hearings remotely through online video conferencing; another alternative is to have shorter trials to limit potential exposure times. Both of these alternatives are viable, but remote participation presents a number of challenges. For example, it could produce panels that exclude citizens who do not own computers or have high-speed internet access, which has implications for juries’ representativeness and diversity. Additionally, compared to standard in-person deliberation, remote deliberation could entail a number of cognitive, social, and behavioral differences in jurors and juries.1 Despite these limitations, COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 courts are currently and will continue to experiment out of the necessity to provide timely justice and address a growing backlog of cases.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Collin County, Texas decided to try a short trial virtually over Zoom, a form of video conferencing.2 Lawyers for each side presented jurors with a brief version of a trial that produced an advisory verdict in a lawsuit accusing State Farm insurance company of failing to cover property damage.3 This was not just an exercise in the viability of Zoom trials; it was also an example of a “summary jury trial.” Summary jury trials (SJTs) are an option for abbreviating civil trials that have been around for several decades.4 Juries in these short (typically one-day) trials issue advisory, non-binding verdicts.5 Their main purpose is to encourage opposing parties to settle and save the costs of a full trial.6 Thus, they are a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR). Although SJTs have not yet been used to any great extent, more and more states have recently begun to realize their potential benefits. In the past several years, states like Arizona, California, Nevada, New York, Oregon, and South Carolina have begun to pilot and implement SJTs in their respective states.7 Other jurisdictions, like Collin County, have also experimented with them on an ad hoc basis.8

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of SJTs. The article describes how SJT programs operate, the variability in their processes across jurisdictions, the benefits they offer, and the drawbacks they present. Finally, we present original data describing judges’ perspectives on the use of SJTs in today’s legal system.

Summary Jury Trials

SJTs have experienced a mixed reception by judges and courts since their introduction in the United States 40 years ago.9 Interestingly, relatively little has been written about SJTs in the last decade, with most scholarship in this area appearing when SJTs were novel, between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s. This makes some sense given that, during this period, summary trials were first introduced in the United States (i.e., in Ohio in 1980)10, were subsequently acknowledged as legitimate by the Federal bench, and were approved by Congress as an appropriate ADR option through the Civil Justice Reform Act of 1990.11 Although SJTs enjoyed some interest across the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, their use was relatively limited, and they nearly seemed to disappear by the 2000s. However, there appears to be renewed interest in assessing the degree to which judicial officers are open to SJTs as a multipurpose alternative dispute resolution method – particularly in light of ever-growing time constraints and budget demands on courts. The sub-sections below describe the varying formats and procedures of SJTs, as well as the potential benefits and drawbacks of their use.

Format and Procedures of SJTs

The American Bar Association defines SJTs as a voluntary process by which “…attorneys for each party make abbreviated case presentations to a mock six-member jury (drawn from a pool of real jurors), the party representatives, and a presiding judge or magistrate,” with the mock jury ultimately rendering an advisory verdict.12 This non-binding verdict gives parties insight into the potential result of a full trial, and often provides a foundation and incentive for negotiating a settlement. Although there is no single method as to how SJTs are conducted, most follow a framework that tends to limit or even eliminate witnesses, that emphasizes exhibits (e.g., documentary evidence), and that temporally condenses the hearing process (e.g., typically a day or less for the entire trial).13

There are a handful of issues of which to be aware concerning the format and procedures of SJTs. Primarily, there is a lack of uniformity in rules relating to SJT procedures, leading to great variation from courtroom to courtroom.14 Indeed, there is much controversy as to whether there should be uniform standards or rules to guide judges and lawyers in these trials, and there is some evidence that judges are sharply divided on this issue.15

First, there is great variation in the duration of SJTs, including the time allowed for each element of a trial (e.g., length of opening arguments). A report by researchers from the National Center for State Courts compared the different approaches to SJTs in six state courts; the approaches were all fairly unique, illustrating the lack of uniformity in process.16 They found that there are no formal rules on trial time limits in South Carolina and Oregon’s SJT programs, whereas in New York and Nevada’s SJT programs, parties are limited to 3 hours to present their case.17

Second, there are no uniform rules for evidence and witnesses in SJTs. In South Carolina’s SJT program, a special referee meets with parties 7-10 days before trial to rule on evidence, and there are no formal rules on including witnesses.18 On the other hand, Arizona’s short trial program permits one live witness for each party and requires all other forms of evidence to be admitted as deposition summaries.19 Relatedly, there are no SJT guidelines outlining what can or should be done if a lawyer takes advantage of the less restrictive evidentiary and procedural rules during an SJT (i.e., can there be a mistrial?).20

A third format variation across SJT programs is the judicial officer who presides over the trial. In some SJT programs, circuit court judges or judges pro tempore oversee the trial.21 Other SJT programs use experienced trial lawyers as special referees to oversee the trial (e.g., South Carolina).22 Similarly, there are no rules dictating whether the judicial officer who conducted the SJT should also preside over the actual trial if the SJT does not result in a settlement.23

A fourth and final procedural difference across SJT programs is how the jury is managed. Although all SJT programs have a smaller jury than traditional trials, there are variations in the size of the jury panel, the number of jurors selected, the number of peremptory challenges, and the proportion of jurors in agreement needed for a verdict. SJT juries typically range between 4 and 8 people selected from jury panels comprised of 10 to 18 individuals.24 Some SJT programs allow parties 2 peremptory challenges, while other SJT programs allow 3.25 In addition, different programs require different levels of agreement to reach a verdict. SJT verdict requirements range from 75% agreement (e.g., ¾ of jurors agreeing) to full unanimity among jurors.26 Furthermore, there is no universal guidance as to whether the jury verdict should be binding or simply advisory.27

Overall, the lack of uniform rules for SJTs results in great variations in format and procedures across jurisdictions. Variations and uncertainty in procedures can be harmful and confusing, leading to challenges and dissatisfaction with the SJT process. To address these concerns, some judges have suggested that procedural rules should appear in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, state statutes, or local court rules.28 An example of this is Nevada’s Short Trial program, which has performed so well at the district court level that the Nevada Supreme Court amended the Justice Court Rules of Civil Procedure to require that the short trial format be used in justice courts29 for all civil matters filed on or after July 1, 2005, in which a jury was requested.30 Although these rules limit flexibility that can be useful to adapt the procedures to each individual case (e.g., case complexity, amount of evidence), there is little question that Nevada’s uniformed procedural approach has been successful over the years.31

Benefits of SJTs

There are many benefits to SJTs highlighted in the literature.32 The primary advantages are the savings of time, money, and court resources relative to a full trial, if the process is successful in prompting a settlement. These savings are related to the condensed nature of the SJT.33 Settlements not only save costs as compared to a full trial; they also help avoid potential appeals and related expenses.34 Importantly, these benefits accrue both to the courts (e.g., time and effort of judges and other court personnel) and litigants (e.g., lawyers’ fees, retaining expert witnesses). For example, a study of New York’s SJT program found that a SJT can cost parties as little as $2,000, compared to $12,000-$18,000 for a one- to three-week full trial.35 With savings in mind, SJTs can also improve access to justice for those who cannot afford a full trial.

SJTs also force parties to hear what an unbiased jury thinks of their case. SJT advisory verdicts often include an idea of a realistic settlement range, and/or suggest whether going to trial is advisable (i.e., one could lose based on how the jury perceived the strength of the case). This type of feedback can make parties more receptive to settlement offers. As noted by the American Bar Association, “…the verdict is frequently helpful in getting a settlement, particularly where one of the parties has an unrealistic assessment of their case.”36

In addition to being less expensive and offering parties feedback, SJTs provide an opportunity for parties to have their day in court and have their story heard without taking a significant amount of the court’s time.37 A day in court gives parties a “voice” in the process – an important known component of procedural justice.38 The process also gives lawyers more experience with juries (an important opportunity for professional growth),39 at a time when jury trials are becoming less and less common40 and an increasing number of lawyers lack jury trial experience.41

In sum, SJTs have many benefits to offer. In a time where courts are exploring approaches to ensure timely access to justice as well as clear case backlogs due to the recent COVID-19 pandemic,42 SJTs could be an effective tool. Indeed, SJTs provide an opportunity to save courts’ resources (e.g., time and money), while also providing parties an opportunity to have their cases heard in front of a jury of their peers.

Drawbacks of SJTs

Although there are many potential benefits of SJTs, they are not without their drawbacks. Primarily, SJTs can be perceived as just another layer of time, expense, and resources that are added to the trial process.43 SJTs are less expensive only when compared to traditional litigation, and only when a settlement is reached. If the parties do not settle, then an SJT necessarily increases the amount of time devoted to the case (i.e., the SJT plus the full trial) by both the parties and the courts.

Another criticism of SJTs is that lawyers feel reluctant to present their arguments and show their trial strategy during what could be perceived as a “dry run” before a real trial.44 There are concerns that, as lawyers become more experienced in conducting SJTs, there could be more “strategizing” – lawyers holding back some of their best evidence or arguments in an effort to surprise the opponent at the “real” trial, should the SJT not lead to a settlement.45 Relatedly, SJTs could be used as a stalling tactic where one party delays the full trial process in an attempt to stress the resources of the other party and force a favorable settlement. Because there are no rules requiring parties to participate in good faith, trust among opposing counsels and the judge is key for SJT participation.46

A final critique of SJTs is that verdicts reached by a jury might not be a reliable indication of the actual trial verdict. 47 In SJTs, there is a tendency to omit background information, due to time constraints, that can negatively affect jury understanding.48 Lawyers often believe that limitations on discovery, such as caps on document requests, prevent them from presenting their case effectively.49 Similarly, many SJT programs do not allow witnesses, limiting the ability of the jury to evaluate the case as they would in traditional trials.50 There can be substantial variance in verdicts among different juries deciding the same case; therefore the verdict of a SJT will convey only limited information about the likely verdict of the real jury that will hear the case if the parties choose not to settle.51 Scholars have argued that SJTs would be more accurate in predicting a trial verdict if they used multiple summary juries, allowed jury deliberation, or used identical jury sizes to traditional trials.52

In conclusion, SJTs can be an effective option to encourage settlements; however, there are several drawbacks that contribute to their limited use. Most issues relate to differences in procedures that make understanding and implementing SJTs difficult. These issues affect SJTs’ credibility as a viable option of ADR, decreasing judges’ and attorneys’ willingness to participate.

Overview of Study

In order to gain a better understanding of SJTs, the current study examined judges’ experiences with and perceptions of SJTs. Researchers outlined four research questions (RQs): To what extent are judges experienced with SJTs (RQ1)? How positive or negative are judges’ perceptions of SJTs (RQ2)? For judges who are knowledgeable or experienced with SJTs, what are the perceived benefits (RQ3) and drawbacks (RQ4) of conducting SJTs? Answering these questions helps elucidate the degree to which current judges’ views match what has been presented in past literature.

Method

Participants

A total of 367 participants submitted a response to the survey. All participants were judges who had previously taken a class at The National Judicial College (NJC). To protect anonymity, no additional information beyond the question detailed below was collected from participants. Therefore, participants’ demographic information is not available.

Materials and Procedure

All data were secondary data provided by The NJC in Reno, Nevada. Data were collected in the form of an online survey administered by The NJC as part of their “Question of the Month” series posed to judges.53 The survey consisted of one question: “Has your jurisdiction tried summary jury trials?” This question was accompanied by a dichotomous yes/no option and an open-ended response section which allowed judges to leave additional information or comments. Completion of the survey was both optional and anonymous.

Coding Scheme

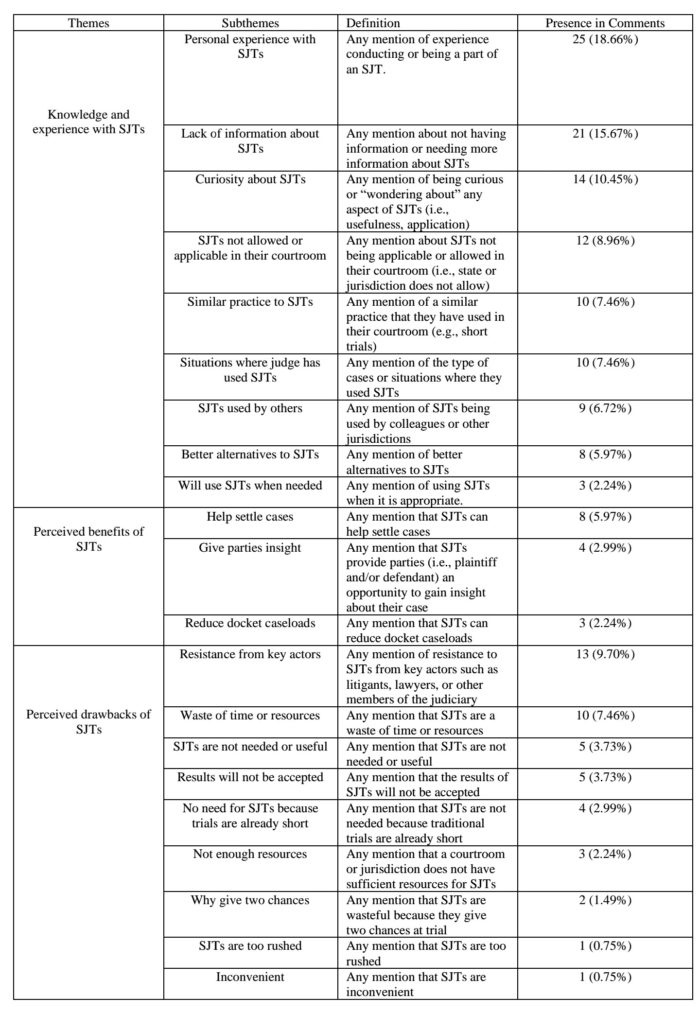

Although judges were not required to comment, 77 judges provided a response to an open-ended comment box. These 77 responses were separated into 134 codable comments. Codable comments consisted of any individual thought that was different from the judge’s other thought(s); many responses included several codable comments. That is, they had thoughts on multiple topics related to SJTs. Judges’ comments were thematically coded for 4 general themes: experience with SJTs, positivity or negativity toward SJTs, perceived benefits of SJTs, and perceived drawbacks of SJTs.

Researchers developed a coding scheme based on themes present throughout the judges’ responses.54 All codes, except perceived positivity or negativity toward SJTs, were scored on a 0 (comment did not pertain to theme) or 1 (comment did pertain to theme) basis. Positivity and negativity toward SJTs, however, were coded on a 3-point scale in which 1 indicated low, 2 indicated moderate, and 3 indicated strong positivity or negativity toward SJTs. Codes were not mutually exclusive, as a comment could have multiple themes (e.g., list a benefit and a drawback of SJTs).

Interrater reliability was assessed to determine whether the raters were interpreting the comments similarly and to reduce subjectivity in coding. Two raters completed an initial coding of 20 comments to identify areas of disagreement and refine coding definitions so that their coding would be as similar as possible. Then, using a random selection of 20% of all comments, two raters independently coded for themes established using the updated codebook. There were 61 codable themes present in the random selection of comments, meaning that one rater or both raters said that the theme was “present.” The two raters agreed on 49 codes (81%). This reflects a moderate to high rate of agreement, given that they would agree by chance 50% of the time. The raters discussed the coding definitions again and resolved coding disagreements to reflect final coding definitions. The remainder of the coding was completed by the first author. See Table 1 in the Appendix for a description of coding definitions and themes.

Results

Experience with Summary Jury Trials (RQ1)

As noted previously, 367 judges responded to the initial question: “Has your jurisdiction tried summary jury trials?” A vast majority of judges indicated that they had not tried SJTs (317; 86%). However, 50 judges (14%) indicated that they had previously used SJTs in their jurisdiction. Judges’ comments provided further details about their experiences with SJTs. Twenty-five judges provided comments discussing their own experiences, while nine other judges discussed their colleagues’ experiences with SJTs. This included discussion of the longevity of the practice in their jurisdiction (e.g., “We have used them for 20 years”) and discussion of the breadth of use (e.g., “I was the only judge in my jurisdiction who did this”).

Ten judges also discussed the situations in which they use SJTs. For example, judges reported that they have used SJTs “in the business court division,” in “complex medical malpractice cases,” and in “automobile accident cases.” One judge explained that SJTs were “required in every case projected to [last] more than 5 days.”

Most judges who responded did not have personal experience with SJTs, yet 35 judges expressed a lack of information (i.e., experience) or curiosity about the practice. For example, judges reported: “[I] would be interested in more info,” “[I] would like to read about how it is conducted,” and “[I] would be interested in knowing how it’s fared in jurisdictions who have tried or are trying it.”

Positivity and Negativity Toward SJTs (RQ2)

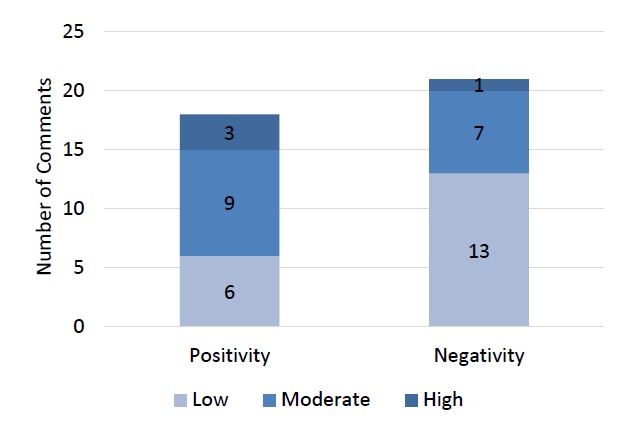

Judges’ comments were coded for both positivity and negativity in order to understand judges’ perceptions of SJTs (see Figure 1). Of the 134 codable comments, 39 comments provided some positivity or negativity toward SJTs. From this subsample of comments, 13 (33%) comments had low negativity, 7 (18%) had moderate negativity, and 1 (3%) had high negativity. On the other hand, 6 (15%) comments had low positivity, 9 (23%) had moderate positivity, and 3 (8%) had high positivity. Thus, the overall tenor of evaluative comments was highly variable and fairly balanced, but slightly more negative (54%) than positive (46%).

Figure 1: Positivity and Negativity of Judicial Comments on SJTs

Perceived benefits of SJTs (RQ3)

Judges reported a few different benefits of conducting SJTs. The most commonly reported benefit of SJTs was to help settle cases. Judges stated that SJTs “…are more effective in some cases than others, but they are undoubtedly an EFFECTIVE settlement tool. We have a high rate of resolution with them.” Another judge explained, “[SJT] ‘verdicts’ were extremely helpful in generating a settlement between the parties in the case.” Additionally, one judge provided a possible rationale for SJTs’ effectiveness: “Sometimes they help settle cases just because they involve a bunch of work that the attorneys and parties don’t want to do so they go settle the case.”

Another benefit mentioned by the judges was the ability of SJTs to provide valuable insights to parties (i.e., litigants and lawyers). For example, judges reported that, “There has been a few judges who quite frequently used SJTs to encourage parties to rethink their posture on settlement.” Similarly, another judge explained that, “Bar members have employed such tactics to sharpen the focus of their cases or to get an unbiased read of their cases.”

A final benefit reported by the judges was the ability of SJTs to reduce docket loads. Judges stated that SJTs would “Reduce case load,” and “… expedite the docket tremendously!” Similarly, one judge viewed SJTs as an adaptation to the shrinking likelihood of jury trials: “I believe that this is the way for the future since I have gone from doing 50 trials per year to 8 over the last 27 years as a Civil/Criminal Judge.”

Perceived drawbacks of SJTs (RQ4)

Judges provided many potential drawbacks to using SJTs in their respective jurisdictions. The most commonly mentioned drawback discussed by the judges was resistance to SJTs by key actors. Judges repeatedly discussed the lack of buy-in from lawyers: “The attorneys, who must consent, have resisted them in favor of traditional jury trials,” “attorneys [are] unfamiliar with [the] concept and [are] unwilling to agree,” and “attorneys never request them anymore, as if the fad ended.” In addition to resistance from lawyers, judges also discussed how litigants resist SJTs, for instance saying: “[litigants] rarely agree to use them,” and “litigants who participate in the process do so only at the urging of counsel.”

Another drawback discussed by the judges was the unlikelihood that litigants will accept the results of a non-binding SJT. For example, judges said, “they will not accept any results short of a full jury trial, and even then, they appeal the jury’s decision,” and “if the hearing is not for real, they don’t want to commit to the process.” Similarly, a couple of judges felt that SJTs give litigants an unnecessary opportunity to have two chances at trial: “Why bother if they can have a further hearing if they don’t like the first outcome?”

A final drawback of SJTs that judges discussed in their comments was the perceived misuse of resources. Many judges reported that SJTs take up valuable time in the courtroom. For example, judges reported that, “In a high-volume court, [SJTs] would require a great deal of time,” and “Summary trials are something that should be used outside of court or scheduled for an empty courtroom without using a sitting judge’s time.” Judges also discussed the efficacy of using resources to support SJTs. Judges reported that SJTs “[Are a] waste of juror resources,” and that “We should put resources into getting verdicts rather than trying to invent the crystal ball.”

Discussion

The results of the survey show a wide range of experiences and opinions about SJTs among the judiciary. Although a majority of judges reported that they have not used SJTs in their jurisdiction, there were 50 judges (14%) who reported conducting SJTs sometime in the past.55 Through thematic coding of the open-ended comments, we learned that many judges (26%) expressed a lack of information about the SJT process or a curiosity about learning more. These results suggest that despite SJTs being an available ADR tool since the 1980s,56 many judges have not been informed about SJTs’ potential as a settlement tool or as an alternative to a traditional full trial. Lack of education about SJTs has been reported as a stumbling block for their use previously,57 and the present data suggest that this problem remains.

Judges who reported having knowledge or experience with SJTs had both positive and negative perspectives on the process. Coding of judges’ comments found that there was a relatively even split among positive and negative comments about SJTs. Despite there being a couple more negative comments than positive comments, the positive comments were more strongly worded (66% of positive comments were “moderately” or “highly” positive) than the negative comments (38% of negative comments were “moderately” or “highly” negative), suggesting that those who have favorable views of SJTs do so more strongly than those with negative views.

When coding judges’ responses for perceived benefits of SJTs, there were many points that were consistent with those previously reported in the literature. Judges reported that SJTs are effective for settling cases, provide valuable insight to parties (i.e., litigants and lawyers), and reduce docket loads. However, judges failed to mention some benefits of SJTs to litigants and lawyers. Specifically, surveyed judges failed to mention the opportunity for litigants to have their voice heard (i.e., have their day in court) or the opportunity for lawyers to gain trial experience through the process of a SJT.

When looking at the reported drawbacks of SJTs, judges also echoed many issues that have been discussed previously. Judges reported the lack of buy-in from lawyers, the reluctance of litigants to accept non-binding results, and the perceived misuse of resources as key issues for the use of SJTs. However, judges in the present survey failed to mention other possible drawbacks, such as lawyers purposefully holding back evidence and arguments during a SJT in case there is no settlement,58 or SJT verdicts not being a reliable indication of actual trial verdicts.59

As with all research, there were limitations to the present study. The primary limitation is that judges were not required to provide an open-ended comment and only 21% of the judges provided a response. Therefore, it is unknown if these patterns of responses would be found at a similar rate if more judges completed the open-ended portion of the survey. We cannot definitively exclude the possibility that those who chose to provide a comment have certain characteristics that may have biased the results. Additionally, no demographic or other individual difference information was collected. This information would have provided a better idea of the representativeness of our sample. Relatedly, we were also unable to determine sampling rates, such as the amount of responses from men versus women or the average length of time on the bench for respondents, which would serve to ensure that our sample is representative of the judiciary as a whole.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides a better understanding of the experiences and opinions of the judiciary on SJTs. Taking the results holistically, it seems that the judiciary is fairly divided on the efficacy of SJTs. A relatively small proportion of judges who responded had direct experience with SJTs. However, there was a substantial number of judges who lacked information and were curious to learn more about SJTs. This finding begs the need for more education on SJTs among the judiciary.

Effective educational programing would not only teach judges the procedures and potential benefits of SJTs, but it could also address some of the reported drawbacks. Although judges reported several drawbacks to SJTs, many of these issues could be resolved with a clearer understanding of the SJT process. For example, the most common reported drawback from judges was the inability to convince lawyers to participate in the process. With a greater understanding of the process of SJTs among judges and lawyers, including the many potential benefits they can produce (e.g., time-saving, settlement), both judges and lawyers might be more willing to employ a SJT. For example, the 8th Judicial District of New York has pioneered the use of SJTs over the past couple decades and has created a Summary Jury Trial Project webpage with videos, manuals, forms, and news articles, all with the purpose of educating those in New York and beyond on the value of SJTs to efficiently resolve disputes.60 Future efforts should focus on providing similar resources and educational opportunities to both judges and lawyers to inform them about the potential benefits that SJTs can provide their jurisdiction.

In addition to education, more formal guidance from either state legislatures or the federal government could encourage judges to adopt SJTs. As mentioned previously, there is great variation in both the format and procedures of SJT programs. Thus, many judges might be unsure which SJT procedures are appropriate for their jurisdiction. If judges were given guidance through training or a benchbook, they might be more willing to try a SJT. This is evident from the many judges in our survey who expressed their curiosity and desire to learn more about SJTs.

Conclusion

Over the past four decades, the SJT has been adapted and implemented to improve civil case management.61 The purpose of the present article was to provide an overview of SJTs, including their various formats, benefits, and drawbacks. In addition, we examined original data describing the perspectives of the judiciary on the use of SJTs in today’s legal system.

Overall, most judges who participated in this study did not have personal experience conducting SJTs; however, many reported an interest in learning more about this unique trial process. Judges’ perceptions of the efficacy of SJTs were also split, with judges commenting on both benefits and drawbacks of the SJT process. Despite the lack of consensus, SJTs seem to be an effective advanced dispute resolution tool for some judges in various jurisdictions. In a time when court resources are strained due to safety stressors and backlogs related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the time could be right for expanding the use of SJTs and further assessing the degree to which they could be effective in maximizing court resources for civil proceedings.

Appendix

Table 1:Thematic Coding of Judges’ Open-ended Responses

a University of Nevada, Reno.

b University of Nevada, Reno.

c University of Nevada, Reno.

d University of Nebraska-Lincoln and Arizona State University. Correspondence for this article should be addressed to Monica K. Miller, J.D., Ph.D., University of Nevada, Reno, Mailstop 214, Reno, NV 89557. Office Phone: (775) 784-6021; Email: mkmiller@unr.edu. The authors would like to thank The National Judicial College for supplying data for this project. Parts of this data were described in a general, non-scientific way in a brief news article published by The National Judicial College. It can be found here: https://tinyurl.com/TheNJC.

1. Brian H. Bornstein & Amy J. Kleynhans, The Evolution of Jury Research Methods: From Hugo Münsterberg to the Modern Age, 96 Denv. L. Rev. 813, 835–37 (2018).

2. See Nate Raymond, Texas Tries a Pandemic First: A Jury Trial by Zoom, Reuters (May 18, 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-courts-texas/texas-tries-a-pandemic-first-a-jury-trial-by-zoom-idUSKBN22U1FE [https://perma.cc/J6CK-58KV].

3. Id.

4. Id.

5. Id.

6. Id.

7. Paula Hannaford-Agor & Nicole L. Waters, The Evolution of the Summary Jury Trial: A Flexible Tool to Meet a Variety of Needs, 2012 Future Trends in State Cts. 107, 108 (2012).

8. Raymond, supra note 2.

9. Thomas D. Lambros, The Judge’s Role in Fostering Voluntary Settlements, 29 Vill. L. Rev. 1363, 1373 (1984).

10. Id.

11. See Civil Justice Reform Act, 28 U.S.C. § 473.

12. Summary Jury Trial, Am. Bar Ass’n, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/dispute_resolution/resources/DisputeResolutionProcesses/summary_jury_trial/ (last visited Apr. 4, 2021) [https://perma.cc/Z9AQ-UBUK].

13. See, e.g., Procedures for Summary Jury Trials before U.S. Magistrate Judge Tom Schanzle–Hankins, U.S. Dist. Ct. Cent. Dist. of Ill., https://www.ilcd.uscourts.gov/sites/ilcd/files/local_rules/Summary%20Jury%20Trials%20Procedures_0.pdf (last visited Apr. 4, 2021) [https://perma.cc/LGU3-WBMH].

14. Ann E. Woodley, Strengthening the Summary Jury Trial: A Proposal to Increase Its Effectiveness and Encourage Uniformity in Its Use, 12 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol. 541, 566 (1996).

15. Id. at 568.

16. Hannaford-Agor & Waters, supra note 7, at 108.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Id.

20. Woodley, supra note 14, at 574.

21. Hannaford-Agor & Waters, supra note 7, at 108.

22. Id.

23. Woodley, supra note 14, at 602.

24. Hannaford-Agor & Waters, supra note 7, at 108.

25. Id.

26. Id.

27. Woodley, supra note 14, at 598.

28. Woodley, supra note 14, at 567.

29. Nevada’s Justice Courts are limited jurisdiction courts that preside over non-traffic misdemeanor, small claims, summary eviction, temporary protection and traffic cases. Justice Courts also determine whether felony or gross misdemeanor cases have enough evidence to be bound over to a District Court for trial.

30. See Nev. Rev. Stat. § 38.258 (2005).

31. See Chris A. Beecroft Jr., The Nevada Short Trial Program, Nev. Law., June 2014, at 22, https://www.nvbar.org/wp-content/uploads/NevLawyer_June_2014_Short-Trial_Program.pdf [https://perma.cc/6XYN-8CBH].

32. See Nino Monea, Summary Jury Trials: How They Work and How They Can Work for You, Mich. B.J., Feb. 2018, at 16.

33. Id. at 16–17.

34. Id. at 17.

35. State Bar of Mich., Alt. Disp. Resol. Section, Alternative Dispute Resolution Compendium, Demonstrating Cost-Effective and Efficient Resolution of Conflicts 9 (2011), https://courts.michigan.gov/Administration/SCAO/OfficesPrograms/ODR/odr-cdrp-admin-site/ReportsStatsOtherDocs/7-ADR_Cost_Study_2011.pdf [https://perma.cc/4UAK-L2RD].

36. Summary Jury Trial, supra note 12.

37. Monea, supra note 32, at 17.

38. Tom R. Tyler, Procedural Justice and the Courts, 44 Ct. Rev. 26, 30 (2007).

39. Monea, supra note 32, at 17.

40. See Campbell, Declining Jury Trials in Civil Jury Project, Jury Matters (The Civil Jury Project at N.Y.U. Sch. of L.), June 2019, https://myemail.constantcontact.com/June-Newsletter-of-the-Civil-Jury-Project.html?soid=1127815376566&aid=AxAN8UsAjrY [https://perma.cc/KSK6-BKSU].

41. Tracy Walters McCormack & Christopher John Bodnar, Honesty is the Best Policy: It’s Time to Disclose Lack of Jury Trial Experience, 23 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 155, 157 (2010).

42. See Charles Toutant, Backlogs More Than Double Pre-Coronavirus Level In New Jersey Trial Courts, N.J. L.J. (June 29, 2020, 5:35 PM), https://www.law.com/njlawjournal/2020/06/29/backlogs-more-than-double-pre-coronavirus-level-in-new-jersey-trial-courts/ [https://perma.cc/Y65L-EHCT].

43. Woodley, supra note 14, at 565.

44. Molly McDonough, Summary Time Blues, ABA J. (Oct. 15, 2004, 7:38 AM), https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/summary_time_blues [https://perma.cc/787S-JHYD].

45. Richard A. Posner, The Summary Jury Trial and Other Methods of Alternative Dispute Resolution: Some Cautionary Observations, 53 U. Chi. L. Rev. 366, 374 (1986).

46. Woodley, supra note 14, at 567.

47. Woodley, supra note 14, at 581.

48. David A. Schaefer, Testing Your Evidence Before and Even During Trial, Litig., Summer 2016, at 1, 4.

49. Steven S. Gensler & Timothy D. DeGiusti, Survey Results: Why Won’t Lawyers Get on the Fast Track? Jury Matters (The Civil Jury Project at N.Y.U. Sch. of L.), Aug. 2019, https://myemail.constantcontact.com/August-Newsletter-of-the-Civil-Jury-Project.html?soid=1127815376566&aid=e6GyPEFbAi8 [https://perma.cc/55RS-7H8K].

50. Posner, supra note 45, at 374 (1986).

51. Id.

52. Donna Shestowsky, Improving Summary Jury Trials: Insights from Psychology, 18 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol. 469, 477–82 (2003).

53. Data were collected in April, 2019.

54. All codes were developed and refined by the first and second authors.

55. It is important to note that many judges who received the survey are not judges who oversee civil cases. In fact, twelve judges reported in their open-ended comment that SJTs were not applicable or allowed in their courtroom.

56. Lambros, supra note 9, at 1371.

57. Woodley, supra note 14, at 609.

58. Posner, supra note 45, at 374.

59. Woodley, supra note 14, at 581.

60. N.Y. State Unified Ct. Sys., Summary Jury Trial Project, NYCOURTS.GOV, http://ww2.nycourts.gov/COURTS/8jd/sjt.shtml (last visited Apr. 4, 2021) [https://perma.cc/ECL5-CFYX].

61. Hannaford-Agor & Waters, supra note 7, at 107.

The full text of this Article is available to download as a PDF.